New Stories

-

Updates

Bike for Prince Archie’s 4th birthday was chosen because it is ‘gender neutral’

The Duke and Duchess of Sussex’s son, Archie, received a Specialized bike as a birthday gift...

-

Updates

No invitation to the King’s birthday parade for Prince Harry

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle have reportedly not received an invitation to attend the King’s Birthday...

-

Updates

Why is Meghan Markle not telling Prince Harry he’s making a fool of himself?

Prince Harry has been on a self-destructive path this year. With his strained relationships with his...

-

Updates

Harry is seen as a ‘loose cannon by Royals while Meghan appears set on destroying’ the Institution’

A royal expert has claimed that Prince Harry is seen as a “loose cannon” by the...

-

Updates

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle are ‘low-grade reality stars’, says Tim Dillon

Popular American comedian and podcaster, Tim Dillon, has branded Prince Harry and Meghan Markle as “low-grade...

-

Updates

Amazon Prime’s Citadel starring one of Meghan Markle’s best friends makes s**ual insult against Kate

The big-budget thriller Citadel, which is being streamed on Amazon Prime, has made a crude and...

-

Updates

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle ‘not welcome’ at historical royal event for first time ever

The Trooping of the Colour, which has marked the British Sovereign’s official birthday for more than...

-

Updates

Prince Andrew reportedly refuses to leave Royal Lodge during building works for fear he ‘might never get back in’

Prince Andrew, Duke of York, has reportedly refused to leave his home, the Royal Lodge, during...

-

Updates

When Prince Harry and ‘embarrassed’ Meghan had a ‘cringe-worthy’ moment at event

Prince Harry and Meghan Markle, the Duke and Duchess of Sussex, recently made headlines when a...

-

Updates

Petition to scrap Prince William’s Prince of Wales title reaches 25K signatures – National

A petition to abolish the Prince of Wales title in the United Kingdom is gaining momentum...

-

Updates

Prince Edward weight loss: Earl of Wessex enjoys diet with ‘popular guilty pleasures’

Prince Edward, the Earl of Wessex, has caught the attention of royal fans lately due to...

-

Updates

Who destroyed Prince Harry?

In Russia, the audience of Who Wants to be a Millionaire rarely “Asks the Audience” because...

-

Updates

Socialite claims Prince Harry has contacted divorce lawyers amid Meghan Markle ‘marriage problems’

Prince Harry has reportedly contacted divorce lawyers amid marriage problems with Meghan Markle, according to socialite...

-

Updates

Kate Middleton Is Reportedly ‘Relieved’ She Doesn’t Have to Fake a United Front With Meghan Markle at Coronation

Kate Middleton is reportedly relieved that she doesn’t have to fake a united front with Meghan...

-

Updates

Prince Harry shares the moment he realised Meghan Markle was his ‘soulmate’

Prince Harry has revealed that he considered Africa as his “lifeline” and the place where he...

-

Updates

Prince Harry thinks he’s ‘smarter than everyone else’: ‘So much ego!’

Prince Harry, the Duke of Sussex, has been accused of having an over-inflated ego and thinking...

-

Updates

Prince Harry’s American dream is ‘collapsing’ amid Meghan ‘marriage troubles’, claims royal expert

Prince Harry’s American dream is reportedly falling apart due to his alleged marital issues with Meghan...

-

Updates

How is brand Harry and Meghan faring in the US?

News just in: not good | Arwa Mahdawi It appears that America’s love affair with the...

-

Updates

Taylor Swift cancels membership at swanky NYC club after pics of date leak: source

Pop superstar Taylor Swift has cancelled her membership at the members-only club, Casa Cipriani in New...

-

Updates

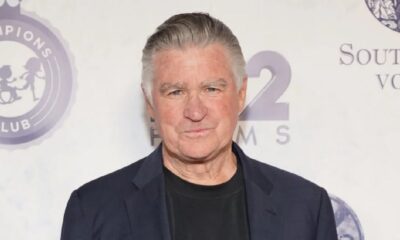

‘Hair’ and ‘Everwood’ actor Treat Williams dead at 71 following motorcycle accident

Actor Treat Williams, best known for his roles in “Hair” and “Everwood,” has died at 71...

-

Updates

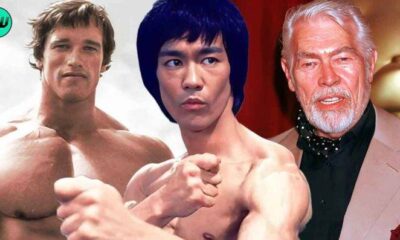

“He was drinking beef blood”: Bruce Lee’s Obsession With Arnold Schwarzenegger Scared His Friend James Coburn

Bruce Lee was an iconic figure in martial arts, renowned for his physical fitness and acting...

-

Updates

The Top 10 Most Controversial CBM Casting Decisions That Worked Beautifully

When it comes to casting for comic book movies, there are always going to be some...

-

Updates

Ben Affleck Was Nearly Replaced by Tom Hanks in $115M Thriller That Was Originally Set to Be Directed by First Ever Female Oscar Winning Director

Ben Affleck has had a successful career in Hollywood, having acted, written, and directed several critically...

-

Updates

“He treats his actors like horses”: Tom Hanks Hated Working With Clint Eastwood While Filming $241M Drama for a Shocking Reason

Tom Hanks’ talent as an actor is widely recognized, and he has worked with numerous famous...

-

Updates

The Expendables Star Jet Li Was Accused of Being A ‘Scoundrel’ Like Jackie Chan for Allegedly Treating Ex-Wife Horribly: “There are a few of these guys in showbiz”

Hong Kong actress Suet Fa recently voiced her opinion on the “scoundrels” of showbiz, accusing Jet...